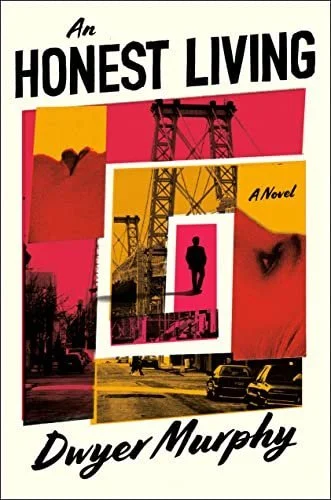

An Honest Living, by Dwyer Murphy

A character driven novel reminiscent of Hemingway.

Can this possibly be an honest story with a lawyer as a narrator? It must be fiction! Yet, the characters in the story sweep the reader into a compellingly honest story, albeit a slow-paced one. No thriller here, or surprising revelations leading to a combustible ending. The novel is genre bending in its combination of romance, a bit of mystery, and interesting characters. All the hype about Murphy’s novel, and there is a lot of it, is only big publisher and media collaboration to sell books. By the way, what exactly is “electricity and dimension,” why would a discerning reader “covet ‘reading in a bar with lousy lighting and good air conditioning?’” The only sincere endorsement is that the book “is a superb debut novel by a supremely gifted writer.” For readers of literary fiction, that is the clue that An Honest Living is a novel worth getting your hands on.

The narrator of An Honest Living, whose name is the same as the author’s, begins his story by introducing Newton Reddick, a character around whom the plot revolves. This is not dissimilar to the introduction of Robert Cohn on the first pages of Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises. There are no real similarities in the plots of the two novels; what is notable is the way that the two narrator’s view themselves. Jake in Hemingway’s novel states up front that “I mistrust all frank and simple people, especially when their stories hold together.” The narrator in Murphy’s novel says, “A lawyer is the last person I would tell my memories and troubles to. That’s what bartenders and parole officers are for.” Both narrators have a knack for describing seemingly unconnected things during events in the plot. Murphy, while standing on a sidewalk with Anna, observes, “across the street, a woman in the second story of a row house opened her window and dropped a bag. It landed in a garbage can and she stayed there a moment, leaning on the windowsill looking pleased with herself, then waved to us and went back inside.” In Hemingway’s novel, Jake swims out to a raft and notes that “a boy and girl were at the other end. The girl had undone the top strap of her bathing suit and was browning her back. The boy lay face downward on the raft and talked to her. She laughed at things he said, and turned her brown back in the sun.”

Dwyer’s characters are flawed persons, although in many instances clever. The female antagonist, Anna, is an unsteady woman, sometimes as practical as a pencil (she’s a writer) but

often skipping between volatility and distractedness. And then there is Ulises, the Venezuelan poet, who appears when a catalyst is needed the get the plot moving, or, in the end, to stop it altogether. All of them have their foibles and their passions. That’s what keeps a reader turning the pages, to find out what will happen to them. What appears is, of course, nothing definitive. And that’s what makes this novel compelling. It’s a very honest peek into a strange mingling of city dwellers, whose paths have crossed in random ways, a law partner leaving a prestige job to hang up a shingle, a novelist trying to escape her husband and her father, and a poet just looking for things to do. Must it all make sense in the end? The narrator at one point mentions that he “dreamed about horse thieves and a posse of old men who were riding after them. I was part of the posse and all we had to go riding on were donkeys and mules, but we were going to do it anyway and that was where the dream ended, with all of us standing around the animals trying to figure out how to saddle them appropriately.” Perhaps Dwyer Murphy intended this as an honest synopsis of what happens in the novel.

The writing in An Honest Living is casually straight-forward, much what one would expect from a former lawyer or a reporter. Murphy has a wonderful style, always getting right to the point when choosing his words, and his imagery is precise, never gaudy. With a single, short sentence Murphy nails down his narrator’s character in a brilliant observation that “There’s a strange satisfaction in quitting a job you shouldn’t.” Jake Barnes expressed a similar succinctness when he said of himself, “It is awfully easy to be hard-boiled about everything in the daytime, but at night it is another thing.” A devoted reader of Hemingway will recognize that Murphy’s style is much like Hemingway’s. Murphy’s writing is marked by a vigorous brevity, and one can’t help believing his characters are real people about whom he is giving a rather pithy account. But Murphy is not yet the great master of language that Hemingway was. After all, An Honest Living is his debut novel. Still, a natural talent is revealed in this first of what everyone hopes is the first of many brilliant works.

For more about Dwyer Murphy, read his interview with Mindy McGinnis here.